April 6, 2024

By Victor Mercado

Under the heat of the Tucson mid-afternoon sun, a small house at 1133 E. Helen sits in the shadow of the massive footprint of the Eller College of Business at the University of Arizona. One building sits high atop a mountain of stairs propped on giant steel columns and showing off row upon row of glass windows. The other is surrounded by a small brick wall and a metal gate that closes with the flick of a latch.

Inside the small house, Dr. Javier Duran and the team at the University of Arizona Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry are investing in the work of researchers, academics and community members who are challenging mainstream narratives and elevating the voices of the people living in and crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

Dr. Javier Duran, Director of the University of Arizona Confluencenter photographed at the El Tiradito shrine in Tucson, Arizona. Photo credit: Dominic Rischard

“We are one of the best kept secrets of the University of Arizona,” says Dr. Javier Duran, director of the center.

Duran’s team is collaborating with communities and scholars along the border reshape the false narratives that surround the U.S. border with Mexico.

“Our brand is built through connection through communities,” says Duran.

For that brand value, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded the Confluencenter $800,000 in 2019 to launch the Fronteridades program. Two years later, it gave the center another $1.5 million, expanding the work of scholars and undergraduates, artists, human rights advocates and community leaders working on changing mainstream border narratives.

Like all things that exist along the border—people, language, customs, music—the word Fronteridades is a hybrid, a mix of la frontera y las humanidades.

“The borderlands provide opportunities for human beings to become resourceful, resilient and creative,” says Dr. Duran during our conversation at the El Tiradito Shrine in downtown Tucson.

In the late 1800s a man by the name of Juan Oliveras married the daughter of a wealthy rancher. Oliveras later fell in love with his mother-in-law and the two had an affair. The rancher, after finding out of the affair, killed both of them. Legend says that their bodies are buried at El Tiradito.

El Tiradito is a place revered by Tucson’s Mexican American community, where the faithful pray for lost causes and light candles for both the living and the dead. Each year, the Coalición de Derechos Humanos remembers migrants who have lost their lives to the Sonoran Desert. This is one of many harsh truths about the desert.

At the same time, the desert has been a source of life for millennia.

The borderlands are places where multiple truths coexist.

Dr. Robin Reineke is a forensic and cultural anthropologist, and a Fronteridades Faculty Fellow in 2021. The fellowship helped Dr. Reineke interview forensic volunteers and civic forensic experts who searched the desert for human remains. Despite the nature of her work, Dr. Reineke pushes back against the narrative of the desert as a place of despair. Photo credit: Dominic Rischard

“There is magic and healing in this space despite the fact that it has become a zone where hundreds…thousands of people lose their lives crossing,” says Dr. Robin Reineke, a Fronteridades Faculty Fellow whose work is helping to bring new awareness to the border. She is an Assistant Research Social Scientist at the Southwest Center and Assistant Professor in the School of Anthropology, at the University of Arizona.

“There are so many layers of history in this space,” says Reineke. “One story that is not right is that the desert is killing people and is responsible for all these horrors of death and disappearance of migrants.”

In fact, it is U.S. policies and law enforcement practices that are responsible for the deaths across the desert, she explains.

“The desert borderlands have sustained life for thousands of years. The desert borderlands are sacred places, providing places, nurturing places that have facilitated relationships and resilience,” says Reineke.

However, distorted narratives have been constructed through U.S. policy. Narratives that she hopes to shift.

The Fronteridades Program at the Confluencenter also funds emerging researchers like Graduate Fellow Juanita Sandoval, whose work seeks to better understand the inner workings of migrant shelters at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“The things that people learn and the knowledge that is shared…giving these stories a voice is really important,” says Sandoval.

A doctoral student in the Teaching Learning and Sociocultural Studies Department at the University of Arizona, Sandoval is researching the role that migrant shelters in Sonora, Mexico play as spaces for both learning and activism.

Casual observers of the border might think about migrant shelters as places of triage and emergency response dealing with a rising global humanitarian crisis. Yet for Sandoval, the albergues are complex spaces.

“I learned about other shelters and how they are connected as systems,” says Sandoval. “They are fascinating places the world needs to understand.”

Juanita Sandoval is a Fronteridades Graduate Fellow researching the ways that migrant shelters can become spaces of knowledge and learning. Photo credit: Dominic Rischard

Funding from the Confluencenter is giving Sandoval the resources to travel back and forth to Sonora to research, and also to attend conferences and present her findings. She acknowledges how difficult it is to find grant funding to study the borderlands. This burden is compounded by the hard things she has to see along the way.

“I have seen a lot of sad things…I met a man who rode the train from Chiapas to Sonora, in Caborca where La Bestia stops,” adds Sandoval.

La Bestia is the name of the train that migrants hitchhike on to traverse the more than 1,400 miles that separate the lush jungles of the state of Chiapas to the arid landscapes of the Sonoran Desert.

Despite the trauma migrants experience, Sandoval calls attention to the ways that migrants in the albergues come together, socialize and even play. She remembers seeing a group of migrants sitting together around a large cooler enjoying each other’s company while playing a game of UNO. A moment of levity and normalcy while playing a game where one’s fortunes can change with the draw of a hand.

Like Reineke, Sandoval also sees beauty in the desert. “The borderlands is an area full of history and cultural knowledge. The space has been inhabited for millennia and has always been a confluence of trade, culture and ideas…it is a very beautiful place environmentally, linguistically, culturally and artistically.”

Melissa Brown-Dominguez, Fronteridades Scholar and co-founder of Galería Mitotera photographed at the historic Sosa-Carrillo House in Tucson. Photo credit: Dominic Rischard

The I-19 highway is a 60-mile stretch of hot asphalt that separates the city of Tucson from Nogales, Arizona, and its sister city on the other side of the border: Nogales, Sonora. Today that same corridor is also known as the I-19 Arts Collective, which is bringing together artists thanks to funding from the Fronteridades program.

An innovative cross-border arts partnership is being forged thanks to participation from faculty from the University of Arizona School of Art, the Museo de Arte in Nogales, Sonora and Galeria Mitotera’s co-founders—Melissa Brown-Dominguez and Mel Dominguez.

The Mels, as they are affectionately known are behind an explosion of local murals, grant competitions and art residencies, and even hosting Latinx chingonas like Latino USA’s Maria Hinojosa at their home in the City of South Tucson, after a Confluencenter event.

Galeria Mitotera, located in the City of South Tucson, made a name for itself in Tucson’s art scene in 2018, filling a much needed void in the Latinx art and culture space.

“The City of South Tucson has a tremendous history: Indigenous history, Chicano, Latino, Mexican history,” says Melissa Brown-Dominguez. “It is so beautiful how communities still hold strong to that. Folks don’t forget about the history and the sense of place.”

Thanks to the generous tranches of funding from the Mellon Foundation, the Fronteridades program at the Confluencenter is infusing creativity into communities themselves, unlike traditional grants that only fund research within the walls of academia.

“We are so grateful for the partnership with the Confluencenter because we are able to reach out to communities of artists that we didn’t have the resources to previously,” says Brown-Dominguez. “We connect artists along the I-19 corridor from Tucson to Nogales, cross-pollinating and getting them to get to know each other and learn. In Nogales, Mexico we are working with a collective of female artists. It started out with four women, and now it’s up to 25,” says Brown-Dominguez.

Melissa Brown-Dominguez thinks of herself as the project manager, while Mel Dominguez is the big dreamer.

Mel “Melo” Dominguez is a renowned street artist who got their start in Los Angeles and now calls South Tucson home. Photo credit: Dominic Rischard

Dominguez explains why the Fronteridades funding is a critical resource, especially for communities and local artists that play an important role as catalysts for new artists coming up in the art scene, “The Confluencenter is putting value on the work.”

“Before it was just me being a mitotex. Me knocking on doors saying, ‘Are you guys still alive in there?!’ The Confluencenter supercharged that ability to focus on mature artists like myself so I can help others invest in themselves.”

Within earshot of Dominguez’s comment at the historic Sosa-Carrillo House during El Sur’s photoshoot, Brown-Dominguez agrees.

“The Confluencenter allows us to dream. They trust us, they see our vision and what we want to accomplish. They remind us that we are doing amazing things. ‘Just keep going!’ they say, while providing us with workshops and training tools to be better leaders and facilitators.”

In 2024, the Mels are doing just that, working with a group of all-Indigenous female muralists that specialize in graffiti. The project will beautify a public housing project to bring life, culture and story into the one square mile City of South Tucson, where its residents have experienced a history of disinvestment for decades.

“We have the ability to tell the story of what’s happening in the borderlands. So much of mainstream media might say one thing, when in fact, there is a whole other story happening,” adds Dominguez.

"The Confluencenter enables us to have that exercise. We are the authors and researchers of our own history and story as it’s taking place.”

Mel Dominguez and Melissa Brown-Dominguez at their home in the City of South Tucson in 2022 with Dr. Javier Duran and a delegation of Chicanx and Latinx leaders hosting Latino USA host, Maria Hinojosa after a Confluencenter event. Photo credit: Galeria Mitotera.

This story was originally posted in El Sur de Tucson.

October 26, 2024

By Victor Mercado

With funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Fronteridades grant, the University of Arizona Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry has created an undergraduate internship program that is connecting college students with community based organizations doing crucial humanitarian work along the U.S.-Mexico region.

Experiences like these are helping students gain a better understanding of the complexities of the borderlands, an area with a rich and complex history.

Last year, the Confluencenter’s undergraduate internship program welcomed eleven inaugural student interns from various academic programs, including the College of Law, Science, Social and Behavioral Sciences, Fine Arts, Humanities, and Eller College of Management.

UA Confluencenter Interns Alivia Alexander, Elisabeth Clark, and Belen Muro Quijada. Photo credit: El Sur

On the one hand, college internships are critical to a student's career development, creating opportunities for learning and getting hands-on experience. On the other hand, nonprofit organizations benefit from undergraduate students' knowledge and skills, creating a virtuous and productive circle for both parties. The downside is that most organizations lack the funding streams to compensate the students, which can demotivate them and make them look for work alternatives where they do not necessarily put their knowledge into action.

This is where the University of Arizona Confluencenter comes in. In addition to connecting undergraduate students with nonprofit organizations, the Confluencenter compensates them for their work.

El Sur sat down with three of last year’s interns Alivia Alexander, Elisabeth Clark, and Belen Muro Quijada, at the historic Sosa-Carrillo House to hear about their experiences and how this internship has helped them develop and grow.

Alivia Alexander. Photo credit: El Sur

Alivia Alexander participated as a 2024 intern with Salvavision, an immigrant rights organization providing support to asylum seekers and people who have been deported by helping them access housing, essential resources, medical care, legal assistance, and financial stability. Alivia is majoring in Spanish and Portuguese and minoring in music and Theatre Arts.

El Sur: Tell us about your internship.

Alivia Alexander: “My work involved keeping track of families' needs. Salvavision provides resources for people who have migrated to the United States, mostly from Spanish-speaking countries, in Tucson and an assistance center in Sasabe, Sonora. The hub in Sasabe is for folks who had to return to Mexico, where some women do embroidery and artistry in exchange for fair wages. In my case, I supported families who live in Tucson. I speak Spanish, so I helped staff with event tabling and whatever my supervisor asked me to help with (laughs). I also designed a brochure with information for people who started moving to the U.S. and translated a legal document.”

El Sur: It sounds like migrant families really appreciated having a person to stay connected with.

AA: “Yes. I called and asked how they were doing, where they were living, what they needed at the time, and what their expenses were. I took notes and translated them into English to show donors how we were helping people. I also put them into a spreadsheet and consolidated all the information in one place for family documentation. Dora, the Director of Salvavision, would follow up with them.”

El Sur: How did you create this information system?

AA: “I would ask them their first and last name and general questions like 'Where are you living?' 'Who with?' 'How many members of your family, and how are you dealing with the process [of moving into the US] in general? '¿Que te hace falta? ¿Que necesitan?' They would say if they needed a lawyer, for example. I would ask them about their legal status. Most of them had been processed and had a sponsor, a few had a work permit, and a large portion sought asylum; they got it but were in court process. They were here looking to get their work permit, somewhere on the way; others needed help figuring out where to start.”

El Sur: Can you talk a little more about your internship experience in terms of your task and flexibility?

AA: “Dora does so much for these families but, at the time, didn't have a centralized place to keep track of so much information. So, I created this spreadsheet with all the information I collected from the families, and it is now categorized. In terms of flexibility, I worked eight to ten hours a week. All my work was directed by Salvavision and was something I did from my dorm.”

El Sur: It sounds like your work has made a huge impact.

AA: “Dora Rodriguez does the most work as the Director of Salvavision. There are five folks who are consistently volunteering and helping people get food, transportation, all sorts of things. They also help people in their home countries sustain themselves so they can keep living there.”

Dora Rodriguez, Director of Salvavision. Phot Credit: Dora Rodriguez

We spoke with Dora Rodriguez one night as she was driving back on State Route 86, which connects Sonoyta, a border town 150 miles west of Tucson.

“Alivia was amazing. We have about 50 families that we support who are seeking asylum, and she gathered all of their information. Alivia called families, gathered data, and tried to figure out their needs and welcome them to this community. She speaks beautiful Spanish, and families were very happy with that.”

Dora Rodriguez is the Director of Salvavision, a nonprofit organization that provides humanitarian aid to asylum seekers and people who have been deported. Fleeing the violence of El Salvador’s civil war in 1980, Dora Rodriguez was one of thirteen survivors who was found near death while crossing the border through the Sonoran Desert.

Rodriguez talked about the challenges migrants face as she drove through the pitch dark desert where she almost once lost her life. She knows how disorienting the desert can be.

"After walking for miles, migrants don't even know where they are," she explains. "Once they are picked up by the Border Patrol, they are processed and deported to the other side of the border to places like Nogales, Agua Prieta, Naco, and Sonoyta."

The conversation tugs on an emotional chord, and she can't help but shift into her native Spanish.

“Es muy triste. Los agentes de migración les quitan su ropa y se las tiran a la basura. Los mandan más que con una bolsita de plástico y su identificación a veces. Hay mucha crueldad, es muy duro,” she adds.

“Estamos con tanto trabajo. Con la repatriación nos están mandando mil personas todas las semanas por la nueva Orden Ejecutiva que entró en junio están siendo repatriadas. Todas esas personas son del sur de México: Guanajuato, Querétaro, Chiapas, Guerrero.

She explains the devastation created by cartels as people flee Mexico, seeking safety. When they are sent back to Nogales, the migrants often don't even know where they are.

"We are trying to figure out how to get them back home," says Rodriguez.

At that moment, it becomes clear just how important the work of interns like Alexander is to the broader narrative of what's happening along the border. I imagine Alexander sitting at her computer in her dorm, clicking away on her spreadsheet, each cell a life hanging in the balance.

“For us, having Alivia provide those hours was really great. I am the boots on the ground, but I need a lot of support. She put all of this information in a file and now we can go back and see how families are doing. Alivia was incredible for us,” she added.

Appreciative of the opportunity to praise her intern's work, Rodriguez is temporarily buoyed by its impact.

"Nos vemos en la lucha," see you in the fight, she says as she hangs up.

El Sur also spoke with Elisabeth Clark and Belen Muro Quijada, who graduated from the University of Arizona in May. In 2024, both were interns with the Arizona Southwest Center working closely with Dr. Robin Reineke on Proyecto Esperanza, an educational resource for families of missing persons in the U.S.

Robin Reineke. University of Arizona Southwest Center. Phot Credit: El Sur

Reineke is one of the leading experts on borderlands forensics.

Missing persons and unidentified human remains have been described as the nation’s silent mass disaster. It is estimated that thousands of families can end up waiting months or years for information about their missing loved ones.

Proyecto Esperanza helps families of missing migrants as they go through the difficult task of trying to locate their loved ones. Based on years of experience supporting families of missing migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border, the Esperanza team provides education, resources, and support free of charge to any family of a missing person who disappeared within the US.

Dr. Reineke explains that for families of those who experienced marginalization due to migration, mental health, or substance abuse challenges, it can be particularly difficult to access the U.S. missing person system.

In addition to providing educational resources, Proyecto Esperanza also serves as a clearinghouse for data about missing migrants and unidentified human remains in Arizona. Project staff collect, manage, and share data about missing migrants with forensic practitioners along the entire U.S.-Mexico border, with particular emphasis on Southern Arizona.

“Working with students like Belen and Elisabeth is my favorite part of my job at the University,” says Dr. Robin Reineke.

“These students brought a lot of heart, commitment, and eagerness to our new initiative,” says Reineke. “In addition to helping us with project tasks, they also contributed fresh perspectives and new ideas that will be baked into the project for years to come,” she added.

Reineke’s research uses ethnography, oral history, photography, videography, digital media, and forensic techniques to better understand communities directly impacted by border violence.

Elisabeth Clark. Photo Credit: EL Sur

This type of work is interdisciplinary, and interns like Clark and Muro Quijada bring complementary skill sets. While Clark brought a background in Anthropology and Spanish, Muro Quijada’s background in fine arts brought a different and equally important lens to this work.

“While at Proyecto Esperanza, I have had the opportunity to learn from others working in this field who have immense experience, knowledge, and compassion to share,” says UA Confluencenter intern Elizabeth Clark. “Doing this work alongside them and learning from them has been the most impactful experience of my education.”

El Sur: It sounds like you were doing lots of upfront work.

Elisabeth Clark (EC): “Usually, we met with Dr. Robin Reineke or Mirza Monterroso once or twice a week. It is a new project. We were doing lots of work with the setup. We reorganized documents and research guides for families of missing migrants. We researched Facebook pages of people doing this work and what this looks like as we start communicating with families of the missing.”

El Sur: How do you explain this project to those unfamiliar with what’s happening along the U.S./Mexico border?

EC: “This is a new project we’re developing at the Southwest Center, a clearinghouse for cases where it’s likely that someone’s loved one has died while crossing. We are focusing on the Arizona-Sonora desert, but we are in contact with other people doing similar work in Texas, like Operation Identification at Texas State University.”

El Sur: What drives you to do this work?

EC: “I started this work and internship at the suggestion of Dr. Robin Reineke. I started to become interested in working with her. What drives me is that because we live in this area, I feel the responsibility of doing what I can. This is a huge human rights crisis, so many people have stories of suffering. If I can do this one small thing and contribute to this project, it’s important to do so.”

Belen Muro Quijada. Photo Credit: El Sur

Belen Muro Quijada, UA Confluencenter Intern.

El Sur: Belen, how did you become involved with this work?

Belen Muro Quijada (BMQ): “I was introduced to this opportunity by my professor from the School of Art, David Taylor, with whom I worked for three years. My work focuses on migration, gentrification, and displacement, and when I heard about Robin and her research work,

I became interested in the Southwest Center and others helping the community and building something. I come from a family of migrants, and I am a first generation, so this topic is very near to my heart and very personal. It's close to home, and I understand it personally. And now, I'm seeing such a broader understanding of other people's experiences.”

El Sur: It sounds like this work is deeply personal for you.

BMQ: “Working at Proyecto Esperanza means I finally get to give back to my community by empowering them with knowledge of their rights and helping them navigate language barriers—something I’ve personally experienced. I’m honored to work with such a passionate group of women who continue to inspire me and give me hope for a brighter future.”

El Sur: How does your background in design inform the work you are doing?

BMQ: “What I’ve been doing is design structuring. My research has focused on how communities have built things like Facebook groups and Pages. Pages can only be posted by the director. With Facebook groups, whoever joins the group can post there. It’s a difference in the control of media being displayed. There is more control with Pages. Directors censor stuff; they are more ethically produced, whereas there are desperate family members who just want to get their family members’ faces out. There are also scams that we have been alerted to. They are using Artificial Intelligence to create these scams.”

EC: “They make a video of their family member from AI taken from photos that they have posted to the Facebook page!”

El Sur: You are seeing this now?

BMQ: “People take pictures, contact family members, and use them to negotiate. They say, ‘I have your family member; he’s safe; he’s alive. Pay me this much money, and we’ll send you this evidence that they are alive.’ They use AI to animate images. We are building this clearinghouse to provide correct sources and alert families of possible scams. Sometimes, they literally crop the face and use a different body. Sometimes they use videos and audio, which is just crazy to us.”

EC: “Families are being taken advantage of because, more than anything, they want to find their missing.”

BMQ: “Their desperation is used to target them.”

As for their future plans, Muro Quijada says she’s going to take a break to get some more experience before applying for graduate school and is appreciative of, “the community we’ve built between our own team and the outside community that we have all built,” she adds.

Clark wants to continue volunteering and points out that finding a community of people working to address the issue of missing migrants was so valuable to her.

“It’s not enough; it’s never enough because people keep dying. But there are so many people who are doing this work who care so deeply. It’s been such a wonderful experience to know that people are doing something,” added Clark.

The Confluncenter is getting ready to welcome its next cohort. Participating organizations in 2025 include the Blue Lotus Arts Collective, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences of the University of Arizona, the Southwest Center, Humane Borders, and the Coalicion de Derechos Humanos.

This story was originally posted in El Sur de Tucson.

By Victor Mercado

Priscilla “Nefftys” Rodriguez

El Sur

Rodriguez parks her car in the parking lot of a place that decades ago was once a Payless ShoeSource and later a stop for Tufesa. There’s lots of places here like that. Reinvention is a trait of Nogalenses, the people of Nogales.

Across the street there’s a taco shop that was once the first Jack-in-the-Box in town.

Rodriguez gets out of the car wearing a black jaket with a hoodie and metallic earrings in the shape of hummingbirds.

Rodriguez is an artist, rapper, and poet. Five years ago, she and a clica of artists—Tony Plak, Gerardo Frias aka Hide (Rodriguez’s husband), and others—turned the twin border cities Nogales, Sonora and Nogales, Arizona into their personal canvas. The public art project was made possible thanks to a University of Arizona Confluencenter Fronteridades grant from the Mellon Foundation. Their work paid homage to the history of Ambos Nogales through a series of murals to bring about a greater public understanding of the border.

“The Confluencenter really started this journey for me,” says Rodriguez.

“They asked a very simple question: ‘How can you tell the story of the border?’I felt like I could do that with history, poems. When I started doing that, I found so much history. Like, I can’t fit it into one piece. It’s really just the tip of the iceberg. I’m really thankful for that opportunity.”

A mural in homage to jazz great, Charles Mingus.

El Sur

In front of us is a large mural of jazz great, Charles Mingus. The mural was a collaboration between Rodriguez and other street artists. Mingus was born just outside of Nogales in Camp Little where his father who was a Buffalo Soldier was stationed.

“Este proyecto hizo que se pusieran las pilas,” this project pushed others to get their act together, says Rodriguez explaining that it later inspired a memorial that was later built near the entrance of Western Avenue by a graveyard. There are a few benches and a mosaic with the image of Mingus.

Rodriguez was part of three border artist teams that each received $30,000 awards in 2020 to support interdisciplinary art projects in border communities.

”I like to create projects and involve other artists. My husband is one of them,” says Rodriguez before switching to Spanglish, “Se junta con el Flak.” He rolls with Flak.

“Priscilla and I met around 2008. We have friends in common,” says Gerardo Frias, 33, over a phone call.

“Out of all the projects that opened doors for us, Nogaleria was key,” says Frias. “We used to do mostly workshops, but this project gave us more space so that other artists would get to know us. We were in Tucson with Ruben Morelos, with the Mitoteras,” (referring to Mel Dominguez and Melissa Brown-Dominguez).

"We have been muralists in Nogales, Sonora doing graffiti in 2008. And this time we wanted to take our artwork to the curios.”

A border cultural renaissance

Mural in Hotel Regis, Nogales, Sonora. Photo Credit: El Sur

Nefftys talks about the cultural renaissance happening along the border, still careful of not taking up all of the credit.

“Not all of the Nogales murals are ours. There have been other murals done by high school students.”

Cross border artists working on a mural outside the Hotel Regis in Nogales, Sonora are challenging the notions of the border as a militarized zone. The murals, vary in techniques and styles, from graffiti to stencils, to projections and free hand, infusing color and vibrancy into the Nogales region.

Though wall space is abundant in a small town where lots of businesses come and go, Rodriguez wishes the City of Nogales did more to support upcoming artists.

“We need more support from the leaders and people in power who can say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the projects. Especially when it comes to graffiti,” she says.

She adds that graffiti is still very much taboo and doesn’t always meet the definition of art. “They think it’s gang related or something that is not artistic.”

Through the Mellon Foundation Fronteridades grant, the Confluencenter at the University of Arizona was instrumental in giving upcoming artists and creatives like Rodriguez and her collaborators the resources to inject creativity into this emerging arts community.

“There’s been a great wave of work that has been done lately with art and new spaces but there is more support needed,” says Rodriguez. “When it comes to government, we need an arts department.”

“I’m a storyteller. I love history,” says Rodriguez. I was inspired to talk about the history of Nogales. Thinking about uplifting Nogales ‘pride’, we focused on murals that would pinpoint historical places.”

Rodriguez takes me to one of the first graffiti projects in Nogales, Arizona that she and her husband who goes by the street name Hideraus helped bring to life. They are located along N. Encino St. near Sacred Heart Church and Pierson High School.

Artists like Nefftys, Plak and Hideraus are elevating street art, expanding their geographic canvas thanks to the generous support of the Confluencenter via the Mellon Foundation.

”The Fronteridades project let us start something.”

The sun as it begins to warm the streets near Downtown Nogales, Arizona.

Rodriguez is a modern day troubadour; poet, artist, rapper.

Before settling in Nogales, Arizona she flew to Europe and toured with a band in Prague. She later spent a few years living in Mexico City, and later honed her musical chops at the Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences in Phoenix.

Her book of poetry, Nogaleria, also sponsored by the Confluencenter, soon followed.

Rodriguez pops open the trunk to her car and hands me several copies, true to her roots as a hip-hop artist used to carrying music samples to promote her latest single.

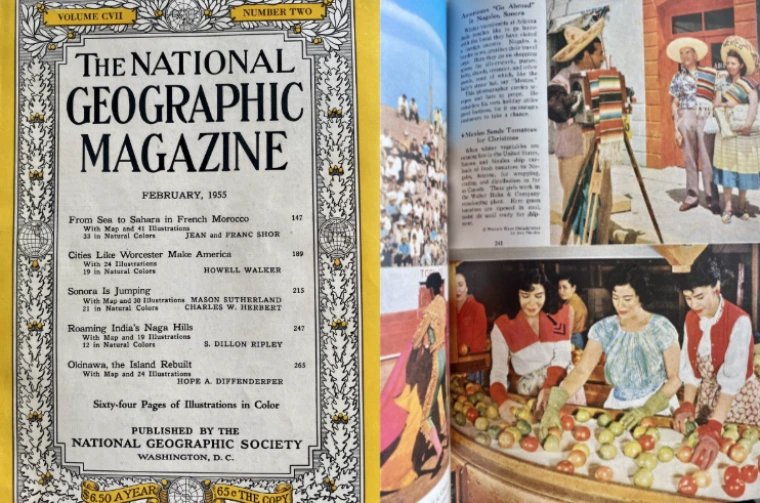

“Did I tell you my grandfather was featured in National Geographic?” she interjects.

Rodriguez’s grandfather (above) taking photos of American tourists in Nogales, Sonora and forever memorialized in the February 1955 issue of National Geographic. Photo Credit: El Sur

Rodriguez tells me the story of her grandfather who in the 1950s photographed American tourists during Nogales, Sonora’s heyday.

Back then tourists from all over the southwest would descend to the tip of Southern Arizona to cross the border and buy arts and crafts, silver jewelry, ponchos, cheap liquor, pharmaceuticals.

Nogales’ mural renaissance is on display on the west side of La Cinderella, one of the longest established retail stores, founded nearly 80 years ago by the Kory family. Inside the store, black and white photographs tell the history of the Nogales, Arizona store which remains widely popular with both American and Mexican shoppers. Photo Credit: El Sur.

This story was originally posted in El Sur de Tucson.